The official arrival of fall is different for everyone. It might begin when you pluck the first apple off the tree. It might start when the first sip of Pumpkin Spice hits your lips. It might arrive after stepping on the first crunchy leaf under your Bean boot. But for me, it isn’t fall until I have my annual read of “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” by Washington Irving.

It’s got everything you could want in a fall story. Charming New England setting. Check. Scrumptious festive feasts. Check. Romance. Check. A ghost. Maybe!

As a short story, I will take this moment to recommend you stop reading this newsletter and go read the story itself (available for free on Wikipedia) or watch the 1949 Disney adaptation (sadly, not available for free, but streaming on Disney+).

Washington Irving is one of the most often overlooked American authors. It makes sense; he wrote under multiple pen names and published in a pre-Civil War America. His writing, while gorgeous, is wordy and can at times be foreign sounding to a modern audience. However, he is an extremely important part of the American canon. You might not realize it but, like Charles Dickens, more than a few Christmas traditions originate from his work, namely A History of New York (also available for free on Wikipedia).

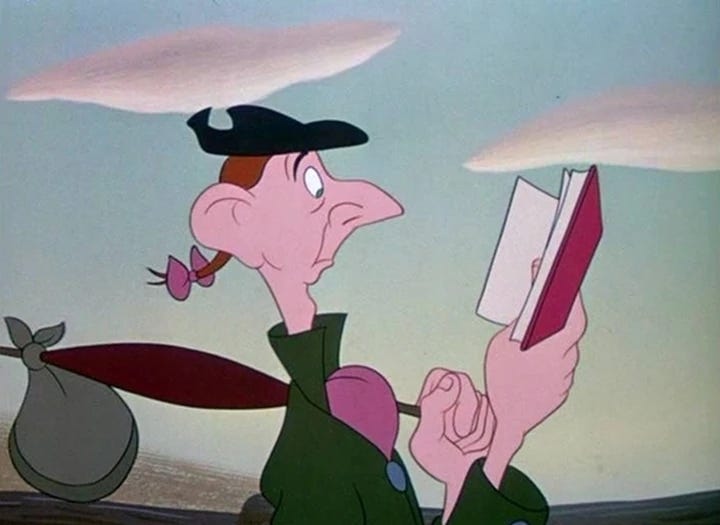

As part of the public domain, there are a handful of adaptations of “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”, including a 1999 film directed by Tim Burton and starring Johnny Depp and a 2013 TV show that aired on FOX. We’re going to focus on the Disney adaptation because it is probably the most accurate to the spirit of the original story. Just read Irving’s introduction of Ichabod Crane and then compare it to the picture below.

“The cognomen of Crane was not inapplicable to his person. He was tall, but exceedingly lank, with narrow shoulders, long arms and legs, hands that dangled a mile out of his sleeves, feet that might have served for shovels, and his whole frame most loosely hung together. His head was small, and flat at top, with huge ears, large green glassy eyes, and a long snipe nose, so that it looked like a weathercock, perched upon his spindle neck, to tell which way the wind blew. To see him striding along the profile of a hill on a windy day, with his clothes bagging and fluttering about him, one might have mistaken him for the genius of famine descending upon the earth, or some scarecrow eloped from a cornfield.”

Bing Crosby’s narration—I did not realize Bing Crosby was the narrator of the short until this week, what a get for Walt four years after World War II!—even pulls choice lines directly from this description.

Not only that, the animators faithfully recreate Tarrytown, the churchyard, the bridge, and Baltus Van Tassel’s farm. One of my favorite details is that the matte painting of the Van Tassel house includes “[b]enches…built along the sides for summer use.”

If there is a question of “Why did we need this?”, there are readily available answers. The animated short introduces a classic of American literature to young audiences, while differentiating itself enough from the original work to have artistic merit by itself. The still nascent art of color animation was the perfect way to create an adaptation. (Disney’s first color short had been made only 17 years earlier).

Disney’s take is much funnier than Irving’s. This is something I think people either forget or never knew about early Disney animation—it’s hilarious. Disney himself was focused on squeezing as many “gags” into all of his films. Obviously, the edges of Mickey Mouse were sanded down, but Mickey was quite the trouble maker. Ichabod Crane comes from that same vein and there are some really fantastic visual gags while Crane and his rival, Brom Bones, are fighting for the affections of Karina Van Tassel, the wealthy farmer’s daughter. The revelry continues to the Van Tassel’s Halloween party where Karina plays each suitor off the other.

Karina is an intriguing character because it is never clear exactly what her feelings are towards either Crane or Bones. There seems to be genuine fondness for both the “itinerant pedagogue” and “the hero of the country round” of “Herculean frame”. Karina could be using Crane to make Bones jealous. I would argue, as the most eligible bachelorette in Sleepy Hollow, she is taking her time to honestly decide between, well, brains and brawn. It takes skilled writing to thread this needle; something Irving establishes and Disney brings to life on the screen.

Speaking of Brom Bones, we are introduced to the antagonist much quicker in the animated adaptation. Disney is less concerned with painting the extended portrait of Sleepy Hollow that takes up the first quarter of the word count. This also speaks to why it’s a great fit for adaptation. What took Irving some 2,000 words can be achieved with a few establishing shots.

For Disney fans, there are fun similarities between “Ichabod Crane”, the opening song of the short, and “Belle”, the opening of Beauty and the Beast. Both walk through their sleepy, little towns with their noses, literally, stuck in books. Brom Bones is very much a precursor to Gaston, from the shape of his face to the color of his clothes to his personality and movement.

It is a fascinating short story; the structure remains quite unique. A lengthy pastoral setting paints a picturesque portrait of colonial America before giving way to the horror-tinged aspects of the finale.

Oh, that finale.

Quite thrilling in both versions, I love how the color palette of the animation shifts. Even Crane’s clothes become a more subdued hue. His forest green pants become mossy, his coat is a pale imitation (pun intended) of his earlier look. It is unclear exactly what happens to Ichabod Crane—in a good way. Focusing on the animated version, there are hints throughout the short. Brom Bones rides a black horse and wields a sword at various times, not dissimilar from the Headless Horseman, but the spirit’s steed appears much larger with sharper and red eyes; the sword equally exaggerated. All that being said, the tale states if you make it to the bridge, which Crane does, you will escape the grasp of the Headless Horseman.

Maybe that’s what makes a great ghost story—you have to fill in the gaps yourself. Our imagination is much more powerful than any words that can be written or any image that can be drawn.

See you next week when we break down one of the greatest twists of all time…

Well written with details to increase the enjoyment of watching a 1949 Disney adaptation. I feel the season is upon us!